In just a matter of days, we’ll come to the high point of the Christian tradition: the resurrection of Jesus. Pastors across the country will stand in the pulpit and use one of my favorite phrases–they’ll remind congregations that not just something has changed because of this resurrected Christ, everything has changed. The pastor I worked with started to talk about it last Sunday: because of the resurrection, “we are Easter people.”

Yet, I can’t help but wonder whether that resurrection life, in our current worldview, is really available to all people, not just in death, but in life.

There was an odd thread this semester connecting the two courses I taught, one on ministry with older adults and the other on young people, and it was the concept of “therapeutic culture.” For older people, this means we live in a culture that attempts to deny aging, because it smacks of weakness, failure, and bodily frailty. In our highly medicalized culture, we use therapeutic techniques to overcome these problems of the body, to fight against not just aging but also death. And we often prefer to live in the denial that we can win such a fight against time and mortality.

In contrast, in her book Chronic Youth, Julie Elman traces young people’s cultural evolution from “rebels” to “patients.” Today the same teenagers who were presumed innately rebellious and disruptive to society have become the object of therapeutic intervention and techniques. We are fascinated by the human brain, by young people’s ability to be conformed to the ideals of society and docile citizenship: the whole goal of adolescence becomes synonymous with young people being rehabilitated from their deficient youthful states to become obedient, accommodated citizens.

In theorizing adolescence through the lenses of therapeutic culture, rehabilitation, and conformity, Elman deftly shows how such a model leaves young people with disabilities behind. If they cannot be rehabilitated or conformed to suit or assimilate or accommodate to society, they cannot become capable, productive human beings.

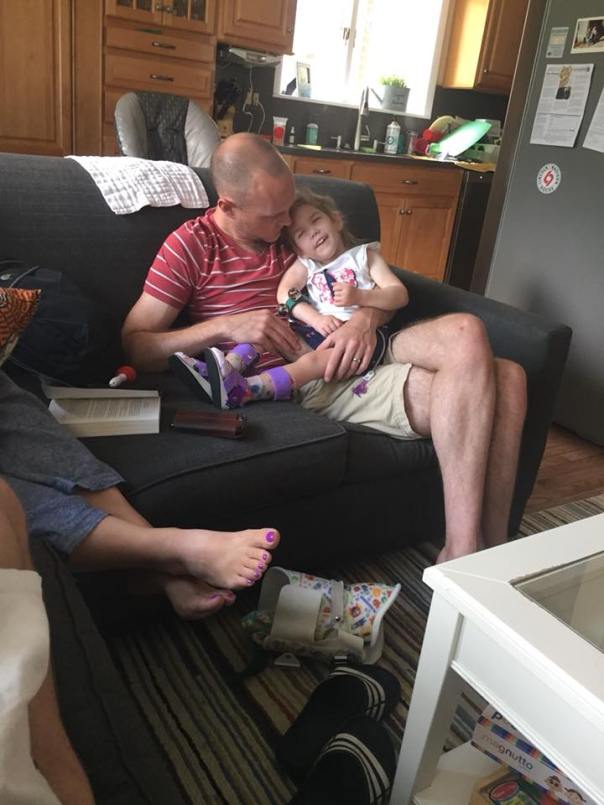

Indeed, Elman’s work led me to puzzle through the concept and purpose of rehabilitation, which is something, as a parent of a child with multiple disabilities, that I’ve always felt uneasy about. When we constantly champion therapy as hope for young people with disabilities, how do we do so in such a way that maintains their integrity as unique and important human beings? When we stress the import of rehabilitation, especially for young people who are born with disabilities, I wonder what we think or hope they are being rehabilitated to? Because there is no prior state of health to often return to, perhaps rehabilitation is a never-ending, dehumanizing pursuit? Perhaps like those who are aging, young people with disabilities become victim to a spiral of therapeutic culture that champions a certain kind of person, a certain kind of life that they can never achieve?

I’ve struggled through this puzzle for so long, because my own child has been the recipient of meaningful, dignifying therapy–the kind that has appreciated who she is and at the same time spurred her on toward substantive goals of social interaction and self-expression. But that doesn’t mean I’m not fundamentally uncomfortable or unsatisfied with rehabilitation as one of the primary metaphors through which we instinctively interrogate the lives of people with disabilities. As anthropologist Gail H. Landsman points out in her study of mothers of children with disabilities, mothers clung to hope in therapy not because they really desired to change and alter their children, but because they thought it more plausible to change their children rather than change the way the world sees them. (A really poignant essay by Maria Rohan in Motherly discusses a similar challenge.)

But this has all got me thinking that if we truly are Easter people, if we truly are the church, we don’t have to buy into the gospel of rehabilitation, because we’ve got different, more transformative gospel at the heart of our faith. Rather than rehabilitation, especially for persons born with disabilities, surely resurrection, as a process of transformation, makes more sense in this world: people with disabilities, like all of us, live within the hope and promise and process of resurrection. They are not being rehabilitated or returned to some prior pure, whole, or able-bodied state, but they, too, are being transformed, made a new, dynamic, empowered, uplifted, exalted creation in Christ.

The problem, of course, is that too often a resurrection gospel has been far too therapeutic when it comes to people with disabilities. People with disabilities are implicitly told that resurrected life is either impossible because they can’t be rehabilitated as “normal,” or only narrowly possible in the hope of a miraculous overcoming or disappearance of their disability in life after death. But this is a false and human dichotomy, coopted by able-bodied imagination, hopes, and fears. This is why theologian Nancy Eiseland gave us such a powerful insight into resurrected life when she drew our attention to the scars and the wounds that Christ still possessed when he was raised from the dead. Christ’s body, imperfectly rehabilitated, yet fully resurrected in our midst, should remind us that signs of life among Easter people may look radically different than what therapeutic culture witnesses to.

And so here I am this morning, longing again, as one is wont to do in Lent, for resurrection in a fallen world. But what I continue to pray is that God would give me the wisdom to behold resurrection, in all its complexity, grace, and abundance. For when we preach of a mere gospel of rehabilitation as Christians we sell short the transformative, life-giving work God longs to do in this world in and through all of us as vessels.

But selling short people with disabilities is not just a problem for them, it’s a problem for all of us. For in a world in which we all grow old and die, therapeutic culture will never win the victory over death that has been won on the cross, a victory that doesn’t just involve the changing of a few lives, but the very world, the conditions, the parameters and limits in which we live. And living like Easter people, in light of that reality, means living with a promise that sees and uplifts and champions life among all people. It means we get to work in ministry that resurrects rather than rehabilitates, that points to who and where God is, even when the world may struggle to understand. And in so doing, that world, especially for people with disabilities, must and will be changed.