Well, we did it again.

We did this thing where we assumed that we could sweep Lucia’s feeding difficulties under the rug, live effortlessly in the unknown, and go about our regularly scheduled lives.

But on the same Monday after a weekend of both smiles and spit ups, even though we got her back to school, my husband and I were both feeling the weariness of acting like everything is okay when your kid’s not okay, of playing along, going through the motions, ignoring, burying, coping…repeat.

This is our life’s rhythm, our girdle of underlying stress that we often do manage so seamlessly that we never have to even acknowledge it’s there, because we calculatedly never move beyond the present. We stay faithful and attentive to smiles and vomiting for this morning, this day, and so, we are okay.

It’s definitely easier to notice the stress, though, creeping up on someone else–how my husband tenses, preps himself with every cough he hears from Lucia. Last night in the kitchen he remarks on the violence in the act of vomiting. As a baby, we watched Lucia struggle to eat, and despite the intervention of this feeding tube that has undoubtedly saved her life, it still often feels like feeding is a reckless and perilous pursuit. After all, aspiration, food entering her lungs due to lack of muscle coordination, all this coughing, and vomiting, could kill her, too. Feeding issues are why she was hospitalized two out of three times last year. And we will never say it aloud to one another, but deep down we both feel so lucky to have not had her hospitalized this year, even though it’s likely that for one reason or another we probably won’t be able to avoid it.

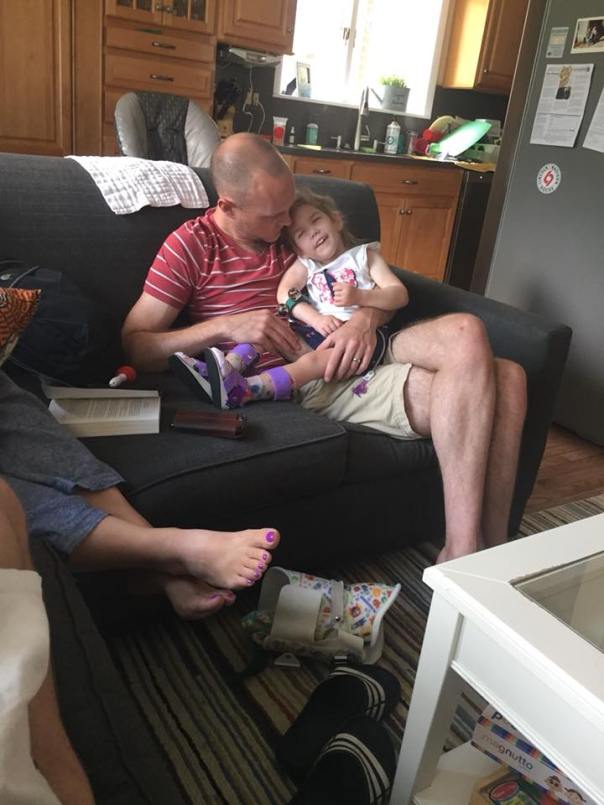

I’m foolishly caught off guard by the stress when I realize it’s there myself–Evan listens patiently to me as I list through everything but Lucia’s vomiting one day, like a woman who’s rustling through her life, yet wholly unsure of what she is looking for. He helps me find it that evening in the kitchen with his willingness to admit, “I think what’s been going on with Lucia has been affecting me more than I thought.” The girdle of stress droops a bit, sags rather than sinches–how good it feels to be found there for a moment. No more searching necessary, for an instant, the three of us are found, held, suspended, even safe.

You see, we’re not inspirations, we’re not superhumans, we just don’t talk about the stress all that much because we don’t know how. We’d just as soon it’d go away and on most days it is faint and pretty insignificant anyway.

But there are days and weeks and even months like these that also remind me that it’s real. There are few relationships I feel like I can be myself in and open up in because of it. There are too many memes and urgings out there to practice self-care as an antidote to it, as if stress is to be prevented or rooted out one cocktail or massage at a time.

But I imagine stress will always be there, no matter how (well or not well) we live this life. As a pastor, when other people tell me how much they hurt losing a loved one or seeing someone they love suffer, I often say to them, “It’s a good thing that you hurt, because it shows how much you care.”

When I read those words, my own words, the tears that never come, start to bubble toward the surface. You mean it’s okay to sometimes feel these things very deeply, to be torn apart and torn up by them, to have good days and bad days? You mean it’s okay to not be okay sometimes, precisely because you love your kid so damn much?

You mean sometimes by acknowledging the stress, we can bear it? That acknowledging it doesn’t mean we magnify fears or betray our children, but rather unearthing fear may be the true antidote to letting it weigh down so tightly?

I don’t know about you, but I often feel like I live my life in incredibly pedantic, redundant circles, and it is so easy to chide–how is it that we’ve ransacked the whole house, only to find what was there all along, was there before, will always be there? And how the hell does that even help matters? But sometimes, it seems, by just acknowledging the stress out loud, we can bear it, we can face it, and facing it somehow disarms it, just a little bit. I felt the grace of that on Monday, that acknowledging stress doesn’t really magnify fears in the way we might suspect it would, and that the best care is not just self-care, but community care, care that holds and suspends and uplifts and acknowledges, and in so doing, disarms but doesn’t trivialize, shelters without saving.

The trouble is, neither Evan nor I ever want to be saved from a life with Lucia–in fact, we want that life more ravenously and deeply than we’ve ever wanted any other thing. We don’t even want it or need it to be perfect, and there’s a lesson in there about love, because it’s not always what we thought it might be, and yet, it’s right where we need to and want to be. So thank you for holding my stress and bearing it for just a moment alongside us–it reminds me that there are more moments like that one in the kitchen if we can be brave and bold to believe and trust that we’re not in this alone. It reminds me that stress is just a portion of a life well lived, so maybe it’s best not swept under the rug–maybe I can share it with you.